I’ve only been doing this blog thing for a couple years now. Yet, it’s been much longer than that since I’ve dived into filmmaking. 2010 was the year I started getting serious about the craft from watching flicks on my laptop in a Berklee College of Music dorm room. Back then I was studying jazz and still trying to pursue music as a career (somehow I thought film was a smarter choice instead.) Nonetheless, one passion culminated into the other. I know these lists have all been subjective, and that’s the point – these lists were never supposed to be the best thing, they were supposed to be my thing. But I still strive to find the greatest common denominators. The 2010s for film probably won’t be as iconic or memorable as films from the 70s, or even the 90s, but leading into this new decade where we’re inundated with new streaming services and content more than ever before, it’s the best time to be a young writer with fresh, new ideas. Here are the top 20 films of the decade.

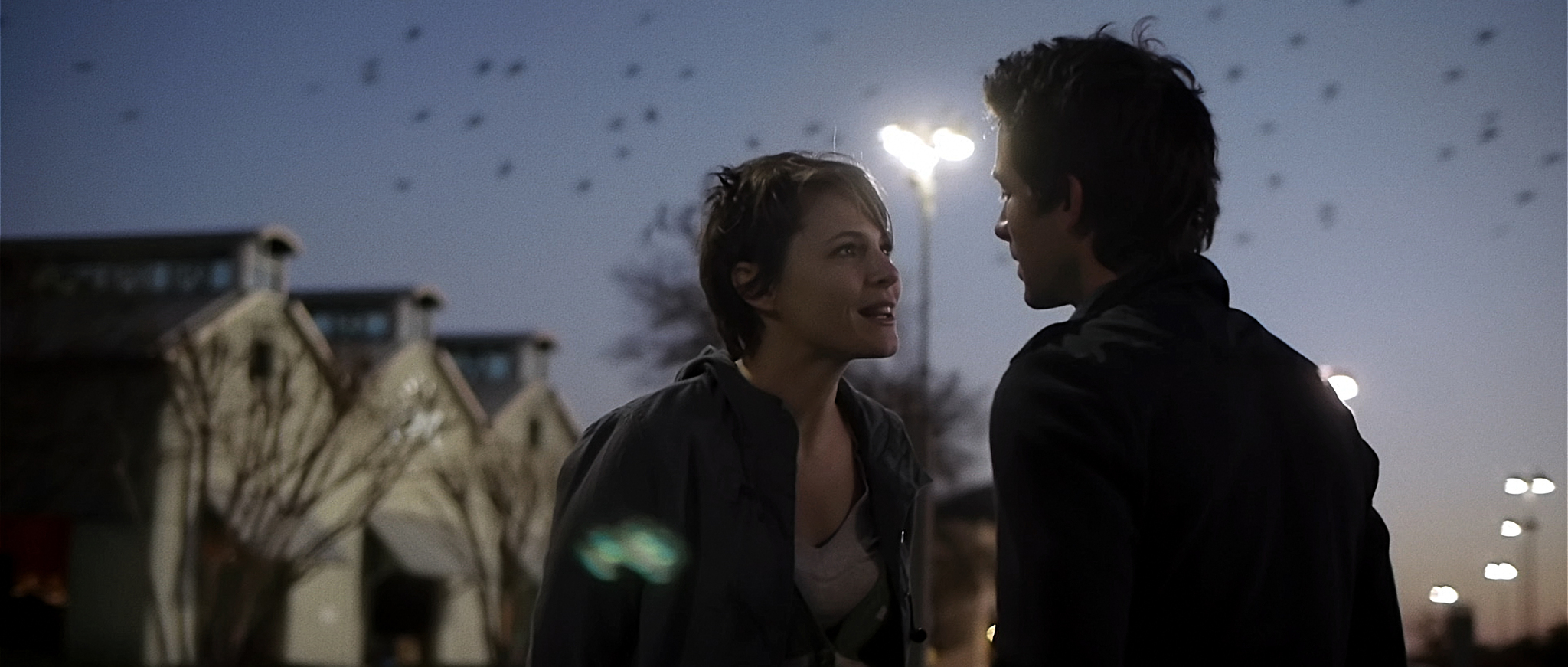

20. Drive

Say what you will about Nicolas Winding Refn, given that he went from the promising art-house auteur who would forge a new path of cinema this decade, to falling so far from his throne and becoming one of the decade’s most crushing disappointments. However, he did shape what would become the eternal vibe of nostalgic synth-pop that would come to rule this decade, which would inevitably become a new form of punk rock. Rumor has it Refn got the idea for Drive from riding passenger side as Ryan Gosling drove him around L.A. nights as electronic synthwave music played through the speakers. The end result was a film that not only painted the aesthetic of the decade that would unfold, but invented a whole new style and atmosphere of 80s nostalgia that would come to rule it. It’s sad to see that this was the last masterpiece he would go onto create in the 2010s, as we all waited for that epic follow up we’d hope would just blow it out of the water. But alas, Drive was too good for that. It was a powerhouse of style and tone that will ultimately be remembered for popularizing that sheer aesthetic. He may not have been able to recreate that charge of energy of what seemed familiar with a new spin, but Drive will stand the test of time exactly for that reason.

19. Oslo, August 31st

It begins as our main character, Anders, is thrusted into a world that he’s all too familiar with. Having spent the last several years in rehab for heroin addiction, he’s granted leave to go back into the city for the day to see friends and loved ones. Yet, the entire duration of the film, we already know what’s on his agenda. On his leave, he goes through routines he probably would have done in his earlier years – he meets with an old friend for coffee, goes to a party where he promptly drinks the glass of wine handed to him, goes to a job interview (one he easily could’ve gotten but storms out of), and drunk dials a former girlfriend who won’t give him the time of day. But he, and the audience, already knows what’s on his mind. He knows the script. Later that night, he meets a cute girl at a party. They go for a morning sun swim, she strips down bare urging Anders to come in. But he already knows what will come. He knows the script of how nights like these turn out. Anders could’ve led a different life. He’s intelligent, resourceful, makes good conversation. He could’ve moved to a new city, a new country, easily picking up where he left off. This is a small film, but nevertheless more poignant than any film ever could be. With a universal honesty, the film evokes an empathy where you don’t have to see exactly where Anders is coming from with drug addiction, but can evidently feel the lost years behind him. Sometimes you know you’ve already swam too far from the shore to turn back. The last thing we hear from him is a sigh of release.

18. Enter the Void

Have you ever wondered what it’s like to die? What it’s like to just lose consciousness where your whole sense of being alive just vanishes? Apparently DMT recreates that experience for you. Or, you could just watch Enter the Void. The film essentially flips the brain switch off for you, creating an experience that you just let take over. It’s a film that’s not too heavy on plot or narrative elements so much as it’s comprised of Freudian images and psychedelic trips. The whole film practically feels like a dream – spliced together images where you, the viewer, assign your own definitions as to how one image ties together to the one that came before it. By now, Gaspar Noé has already deemed himself the punk rock filmmaker of this decade with Love and Climax, but no other film of his challenges what the medium can do in terms of stretching its boundaries reaching far into the human psyche.

17. Inside Llewyn Davis

As I write this at this moment, I’m sitting up on an air mattress in a friend’s living room in Prospect Heights, Brooklyn. A heater right next to my head keeps me warm, as the apartment’s dwellers have all left for work on a Monday morning. It’s moments like these where I occasionally think of Inside Llewyn Davis. This one has still remained somewhat of a mystery to me among the Coen Bros. filmography, but it’s one that nevertheless has stuck upon first viewing. When I watch it, I think of all the friends couches I’ve slept on and called in favors for. I think of the bitter cold of winter when I ask to crash wherever. I think of the soft lens glow from the filter used by Bruno Delbonnel. And, of course, the circular nature of it all, how the end comes chasing back to the beginning, making you feel like you’ve really never left but have been moving in the same space for a while now, despite little or no progress. Rumor has it that the Coens didn’t really have a finished script until they added the cat into the mix, which eventually becomes the only constant in Llewyn Davis’ life. It makes me think of how life can kind of feel like it’s just passed you, like the youth of a younger individual stuck in an older person’s body. It evokes nostalgia without all the emotional baggage that usually accompanies it. It makes me think of all the people I’ve known, everyone I’ve ever met, regardless of how long they’ve taken part in my life, and I just think, “Wow. I’d really like to see them all again.”

16. Her

In a futuristic version of Los Angeles, dating gets a whole lot weirder. But I won’t spare you the details because I already assume you kind get the gist of Her. What made Her so special when it came out was that you knew exactly what you were getting into: Joaquin Phoenix falling in love with a computer. But when you walked out of it, it felt much deeper than what was presented on screen. The film questions the ideals of love, striving to point out what it means to love, and what you can love. It erases the boundaries of normal romantic comedies placing emphasis on trusting one’s feelings and what it means to strip away identity. And if there’s any acknowledgement as to which actor truly reigned supreme this decade in changing what acting is capable of, it’s Phoenix. His performance grounds this film, acting on different levels of conscious acting, unconscious, and sub-conscious, bouncing off Scarlet Johansson’s voiceover work and anchoring this narrative with every little inflection from his eyes. I remember this movie topped a list of the scariest films of 2013 because of what the film implies about the future. However, I don’t think it’s scary at all. Rather, I see it as a testament of how love can be defined.

15. Uncle Boonmee Who Can Recall His Past Lives

Enter the David Lynch of Thailand. The first Cannes Film Festival winner of this decade set out a strong precedent of what would be a run of great meditative films from Apichatpong Weerasethakul. It’s a film that’s not supposed to be easily digested, rather, you simply let yourself understand it instead of trying to understand it. There are no close-ups in this film, no use of micro lenses to close in on keen details, but that’s not to say that this film has no attention to detail. Rather, it focuses its attention on every detail by just letting the camera hang back in mostly wide shots, not giving any character or piece of set design more attention than the other. The result shows how life and death is perceived in Southeast Asia. Life is not seen as one linear narrative, but as a circulatory journey, coming back as souls in another life. By not giving too much attention to any character, Uncle Boonmee acknowledges that every being in every frame of this film is a character. Every inanimate object has a soul, everything acts on an equal playing field, making you think twice before swatting the next fly.

14. Holy Motors

It’s crazy to think that some films can’t be “explained.” That is, they can’t be tied up neatly into a bow and labeled in a box. Some films are beyond genre. Hell, some don’t even abide by logical narrative roles. Holy Motors could possibly be considered such a film. The film follows Denis Lavant as he goes throughout a single day in Paris, taking on different roles and disguises in various role-playing situations. We don’t know his agenda or his endgame, but merely the fact that he does this for “the beauty of it.” But what ends up happening is that the film serves as a love letter to the medium of film itself. The film starts with director Leos Carax entering a movie theater which immediately transports us into the world of our main character. And what follows is an exploration of the many forms the medium can take shape: CGI, 16mm, Super-8, high-def, animation… Denis Lavant’s character is merely used as a vehicle to explore all these formats, and in turn, serves as an homage to the power of film.

13. Tree of Life

Interestingly enough, after making a film about once every decade, Terrence Malick has made more films in these past ten years than he has in his entire career. However, of all of his projects from the 2010s, Tree of Life will not only stand out as his best from this decade, but the best of his filmography. From using footage that was shot over a number of years to using real life NASA footage of the cosmos and CGI (the dinosaurs!), Malick finds a contrast of just the right elements to make the film feel like it’s a whole greater than the sum of its parts. The result leaves a lasting impression from creating a world not just out of, of all places, Waco, Texas, but uses that setting as the blink of an eye within the grand vastness of the universe. We exist as just a spec of dust through this every expanding macrocosm, and the film emphasizes the emotion of it all imploding in on us when it feels too much. 60’s Waco is used as the center of this film, but that’s beside the point, because this film serves to a story that could’ve taken place at any moment, at any place in time.

12. Zero Dark Thirty

The importance of Zero Dark Thirty when it came out was not to shed light on torture tactics, nor spoil the novelty of having Bin Laden assassinated. It was pertinent, however, in pointing out the drastic measures our federal government, security, and society at large, have adapted to live in a post-9/11 world, which is truly where this script shines. Each inflection from every character, every line of dialogue, seems to stem out of some sort of fear within every character (note when Jay Duplass’s character suggests to Maya that she should “maybe stand in the back” when Secretary of Defense Leon Panetta arrives, to which she responds “I’m fine right here thank you.”) Every measure taken by a character in this movie acts toward assuring the safety of our nation, which brings us to the last shot of the film, as a single tear shed represents not the end result of the assassination, but serves to highlight everything we’ve sacrificed as a nation to get to that point – every inch of privacy, all the lies and torture and cover-ups we’ve been fed, all to insure our nation’s domestic tranquility.

11. Get Out

I could write about the political and racial implications of this movie. I could write about how it was only a matter of time until a modern horror film was told from a black-centric point-of-view, or how 2017 was finally the year where we began to not label films and put them in a specific category. But what will make Get Out stand the test of time is simply how well done it is – an air-tight script with earless and unapologetic direction that knows exactly what it is but knows no limits. The attention to subtle details, the specifics of its implications (she separates the white milk from the colored cheerios!), everything serves to its central theme. By just watching the film or even reading the script, you can practically tell how much time Jordan Peele spent on writing it, to the point where you can see the layers upon layers of details and callbacks and re-writes within the script. But above all else, the movie is a testament to pure talent, a testament that great work will transcend any political or racial stereotypes and boundaries.

10. The Act of Killing

How does one take mass genocidal criminals and convince them to reenact their murders in any way they please? Well, you simply get them to recreate some of their favorite films from growing up. Joshua Oppenheimer’s haunting portrait of the dark side of human capabilities resonates as one of the most intense movie going experiences of this decade. With a crew that mostly remained credited as “anonymous” so as to not expose their identities to the Indonesian government, the film portrays the mass murderers’ verbosity of their killing of millions of communists in 1960s Indonesia, recreating the killings in ways they deem fashionable through movie scenes. However, as their levees break and fear takes hold, we see the murderers come to reality in real time, finally putting themselves in the shoes of their victims. It’s a documentary that’s both hypnotic and dumbfounding, reinforcing a principal that all too many of us seem to forget – it’s easier to kill someone when you don’t think of them as human.

9. Moonlight

The answer to surviving 2016 wasn’t escapism, but empathy. The use of subjective camera in Moonlight brought to mind Jonathan Demme’s work, or even Magnolia, in which Barry Jenkins casted for faces, not only making these close-ups “glow,” but provided an empathetic vessel so as to subtly put the audience in the character’s shoes. But aside from the close-ups, what immediately springs to mind are the filmmaking techniques Jenkins borrows from to capture all of this – from the spinning long lens shot before Little’s fight with his bully that echoes The Good, The Bad, and the Ugly, to the ocean scenes where Juan shows Little how to swim that quite bravely borrows from Clair Denis’ Chocolat. Everything you need for a film school lesson is there. But what can’t be taught is Jenkins’ perspective of it all and his world view. When we see these aura-glow subjective close-ups, he’s not only asking us to empathize, but to not judge a face by its color.

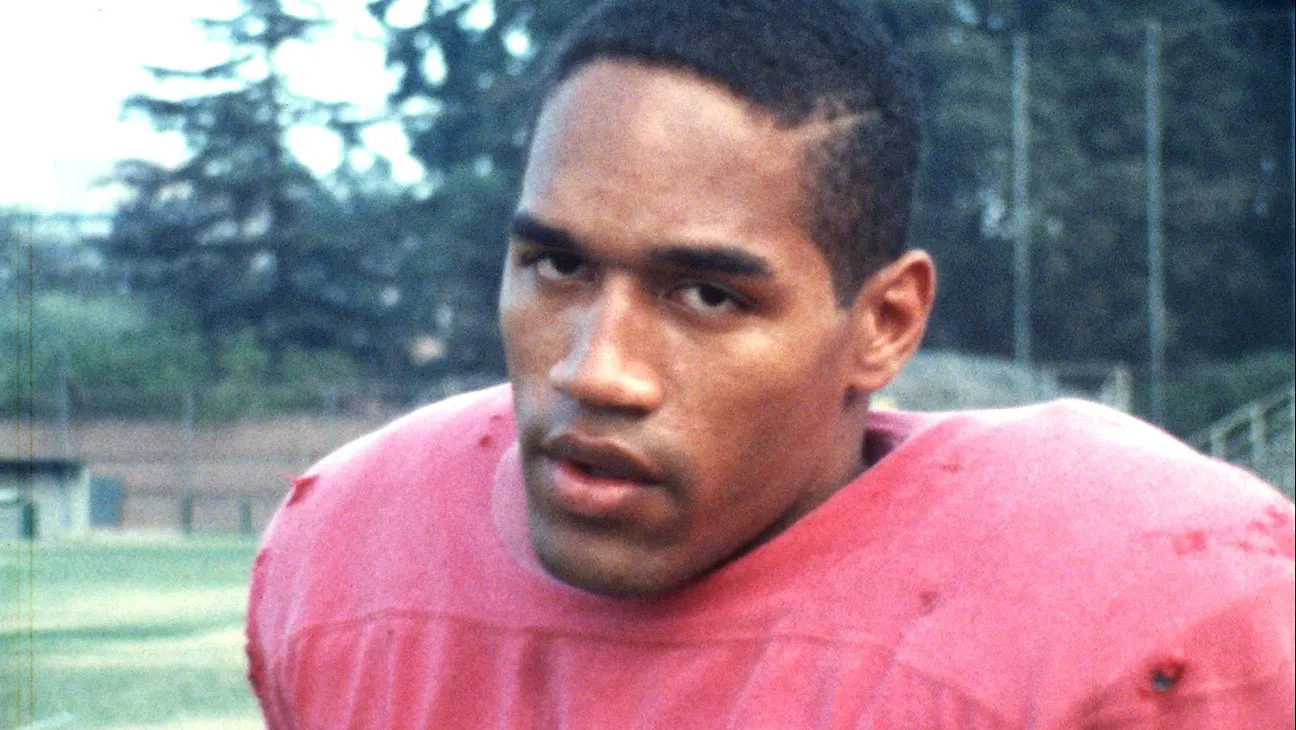

8. O.J.: Made in America

Much is to be said of this sprawling, eight-hour, five-part documentary on the rise and fall of O.J. Simpson. However, when I think back on this doc, the figure and personality of O.J. Simpson is secondary to me. Instead, I think of the sprawling racial portrait it depicts of Los Angeles, using the O.J. court case as merely a vessel to further explore a divide that runs much deeper than what the trial brought forth.

O.J. is only used as a reflection to see the inner hate we find within ourselves. O.J. didn’t deserve to be found innocent and be forgiven by the black community, only to be arrested once again after not having learned a thing. It’s a documentary in that the cinematic experience conjured in our heads only makes us turn and look within ourselves to find that we can be so consumed by greed and revenge, that sometimes we end up being the monsters.

7. A Separation

The beginning of A Separation is what makes the film so taught. It immediately gives us the start of the story, the set-up, and the stakes that will be in play, which is sustained through the entire film. It’s a masterclass in scriptwriting and the progression of a narrative, where the circumstances and jeopardy reach so high it’s impossible to look away from. Following a wife who sues for divorce over assuring a brighter future for their daughter, she moves in with her parents while the father stays behind to look after his sick father. When a chance accident happens with the father’s caretaker, the family is thrusted into legal woes that they can’t step away from. It’s a searing, slow-burn family drama that demonstrates that the legal system does not account for human feelings, nor does it abide by religious values. It’s a film that progresses with conflict after conflict, leaving the child hanging in the balance and making us wonder how such a legal system can exist if it’s only meant to tear families apart.

6. Burning

Having topped last year’s “Year End” list, Burning’s mysticism still lingers amongst the best of this last half of the decade. Based on a short story by Haruki Murakami, the film follows a young “writer” who must overcome the limitations and hardships placed upon him by his family and class status. Anchored by a villainous performance from Steven Yeun, our lead character, Jong-su (Ah-in Yoo), can’t help but feel as if the universe is working against him, or if he has the power to change any of it. It’s a searing slow burn of a film, all building up to a climactic third act so staining it’s hard to pull the images from your head. The film plays with our temptations of what we can or cannot get away with, heaving us to our burning desires until it swallows us whole, leaving us no choice but to take risks to escape and burn it all down.

5. Under the Skin

Under the Skin will be remembered by not what it does, necessarily, but what it doesn’t do. That is to say, the title implies exactly what it wants the audience to do – it compels them to question if there’s something deeper to this movie. I could go on for paragraphs about how this movie was (and still is) a game changer – how Jonathan Glazer developed his own cameras for the van scenes, or how they used real life pedestrians and non-actors so as to get a real-time reaction when Scarlett Johansson pulls up and seduces them – it’s the small, subtle things this movie does that makes the audience question what it’s about, all tethered and motivated by possibly the greatest film score of this decade. By the end of the first viewing, you’re left thinking “What? Is that it? Nothing happened.” But that’s exactly what the title suggests: is there more beneath the surface? Is there more this movie hints at than what’s presented on screen? This is not a narrative-minded conscious film, it’s not a film that you just read like a book, because it operates on another level. Take all that into context, and you’re left questioning what the events in this film truly represent, particularly the ending, which leaves the destiny and fate of humanity in question.

4. The Master

Paul Thomas Anderson returned from a five-year hiatus with a film that was shrouded in even more mystery than his last. Much was kept under wraps for months during production leading up to its release, with everyone referencing it as “that scientology movie,” when in fact the movie never mentions scientology once. However, that only fed fuel to the fire. The film teeters on the balance between two extremes of human civilization, one played by Lancaster Dodd (Hoffman), and the other Freddie Quell (Phoenix), and the vast sea of human possibilities with which human evolution can take shape. This was one of the more polarizing films of the past decade with a fine line drawn down the middle of the audience separating it into two bodies: those who were frustrated by it and hated being frustrated by it, and those who were frustrated by it but enjoyed the struggle of understanding it as such. But what makes it so captivating is the hypnoticism of it all. PTA plays with the medium of film for the love of the medium itself. The film pushes the boundaries in terms of what cinema can reach, what it’s capable of. Shot on 70mm, the film becomes so tangible that it’s the closest thing to 3D without the 3D. You can feel it, you can taste it, you can smell it… But what is The Master really about? Can anyone really tell us after all these years? Surely, many people will disagree on the topic, but to my understanding, it’s about a failed relationship from the get-go, doomed to never see eye-to-eye due to the vast extremes of civilization the leads come from.

3. Upstream Color

What makes a film’s release strategy so exciting are the rumors that surround it all. No one knew what Upstream was about leading up to its debut at Sundance in 2013. And upon its premiere, people still couldn’t decide what it was about. But a Time Magazine headline from that night summed up the entire mystery – “Did one of the best films of all time just debut in Park City?”

Shane Carruth’s follow-up to 2004’s Primer wasn’t the dialogue heavy sci-fi drama his debut film was, but something that acted on another level, something akin to 2001 or Enter the Void. People still argue what it’s about today – but to sum up this humble writer’s opinion of what it all means, it’s about stripping away identity, any politics or pre-existing scars on the surface. But what made it so game changing is how Carruth brought it to audiences. Taking the reins for every creative role involved in the film, Carruth decided to four-wall it, which is to say, take the film to individual theaters across the country to generate revenue, and then continue onto the next theater, which is probably what made this film so special – it was virtually untouched by Hollywood. It’s hard to believe now that, given the film’s thrifty budget and how deep it explores the human senses, Carruth has been struggling to get his next project made. Last we heard of him was that he was prepping a film titled The Modern Ocean, which had A-list talent attached (Anne Hathaway, Keanu Reeves, Daniel Radcliff). He had a small stint doing music for The Girlfriend Experience, and a small cameo in Swiss Army Man. But now he’s virtually undetectable. But that’s what makes him arguably the most exciting filmmaker on the planet: the fact that he still has his best work ahead of him. I heard he and longtime partner/Upstream co-star Amy Seimetz separated this year, which makes this film all the more poignant. I’ve also heard a rumor that he’s retired form filmmaking altogether. Regardless of the truth, Upstream achieves what all films wish they could do: evoke empathy through the senses. And even if Seimetz and Carruth’s working relationship has come to an end, it doesn’t mean what they had wasn’t real. That’s what this film is to me – the flourishing of something real shared by one another regardless of circumstances.

2. Dogtooth

Yorgos Lanthimos has had a decade-long trek in becoming one of art-house cinema’s titans and absolute awards favorite with The Lobster, The Favourite, and Killing of a Sacred Deer. However, he began the decade with a film that everyone will immediately think of when his name is mentioned – Dogtooth. It’s incredible to think that such a contained, specific vision would lead to one of cinema’s most deserved career flourishings. But what makes this film standout amongst his filmography is the essential wholeness of it. Everything his films embody, what they all tackle, what they all set out to explore, all come to a head in Dogtooth. Shot primarily on a 50mm prime lens, the film frames a portrait of a family as if you were looking at old childhood pictures, but can notice something deeply wrong and troubling behind them. And on the smallest scale possible by being contained in a single home, the audience is never one step ahead of the film, but rather, the film leaves us miles behind. It all acts as a Petri dish effect, doing what his films do best – explore the basic elements and nature of human behavior.

1. The Social Network

It’s crazy to think that, only nine months into the new decade, we already had the decade’s best film, but it took ten years to see it as such. What began the decade as a promising future in mass communication and commerce, ultimately ended the decade in what looked like anything but. Many chastised The Social Network for painting Mark Zuckerberg in a bad light. Now it could be chastised for not painting him in a bad enough light. What started as a prosperous growth signaling how we’d communicate and interact in the future ultimately ended up becoming an enemy to democracy at large. Ever since its release, it drew numerous comparisons to Citizen Kane, and that’s not entirely wrong. However, I think The Social Network takes one step beyond that, where society thinks about their plans ahead of time and how they’d go about their everyday lives to impress people or talk to that one crush. It’s changed lives for the better, and for the worse. But look at how we live now – we live in a world so tapped into the greater web that we know who someone is before we even meet them in person. 15 years ago, that was unheard of. But now it’s the norm. Take a look at how this film embodies all that – the use of windows as separation, shallow depth-of-field, the Nine Inch Nails score that layers modern day electronics over classical instruments… it draws a portrait of what was supposed to be a gift of endless reach and unification to the world told through the eyes of the individual who only ended up cutting himself off from it.

There are many moments we can associate this movie with: where we were, who we were, where we were going. But the one thing that immediately stands out to me is that it shows we live in a world where every piece of information and history is available at our fingertips, yet we don’t have the power to change any of it. It’s difficult to capture something so fleeting, so ephemeral, so intangible. But I always come back to that final shot which manages to capture all of that, as the computer mouse hovers over the “Request Friend” button. And then we refresh, and refresh, and refresh…