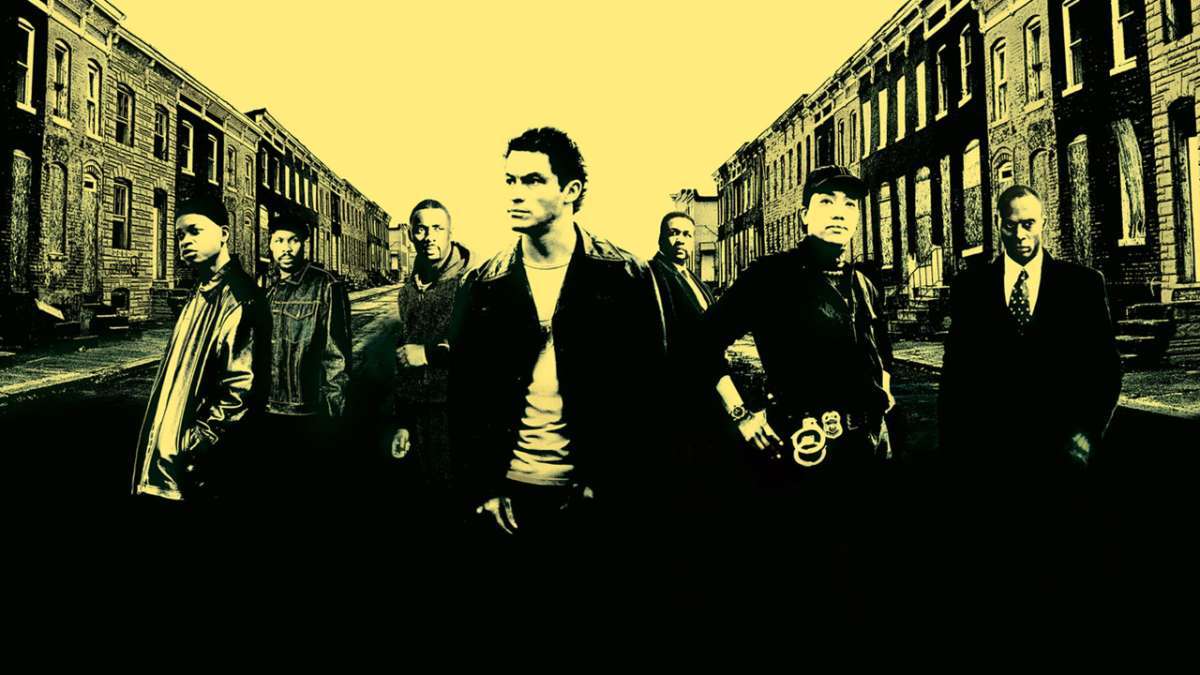

Every once in a while, The Guardian or Rolling Stone will put out a list of the “100 Greatest TV Shows of All Time” or something along those lines. The Wire, more often than not, always lands near the top. It was ranked 1st on Entertainment Weekly’s list, and the WGA ranked it as the 9th greatest show ever made. However, it won zero Emmys, was always dwarfed in ratings by HBO’s other darling The Sopranos, and very much like the oppressive nature within the show, it struggled and fought to get renewed each year. But it’s the only show I know of that tackles real world problems in the landscape of urban development.

Eighteen years ago, Detective Jimmy McNulty came across a murder in the first minutes of the series. The first sequence immediately sets off a string of events that reverberates through all five seasons, plunging us straight into the inner workings of a corrupted system. Throughout the series, we’re exposed to corruption on varied levels of the urban landscape (the city’s ports, the mayor’s office, the school system) and how this theme of corruption seeps through into every level.

From its reshaping of procedural dramas to inclusion of colored LGBTQ characters, the show laid the groundwork for what much of TV builds itself on today. It begins with its form of longevity. Traditionally, we think of cop shows as procedurals, that is, standalone episodes with a case of the week, a new bad guy every episode. The Wire turned that formula on its head. Instead of focusing on one case each episode, they focus on a different component of the same case in each season, each one stemming from the same source – the city’s drug trade.

It begins in the first season when McNulty sees a witness go back on her story in court. He brings this up to the higher powers who are reluctant to further investigate, and stick McNulty and his squad in the shitiest of basement offices to work out of. They investigate the Barksdale family drug ring in West Baltimore, in which they soon discover that this ring is ground zero for corruption in the entire city. Now rallying against the higher ups who refuse to give them proper funding and resources, they must fight for their investigation’s credibility. This is the first sign of corruption that sets off the ripple-effect throughout the series, and by being thrusted into this investigation, McNulty puts his coworkers’ reputations, lives, and his own family-life at risk.

With its sprawling cast, we see all these different components at work in tandem with each other from around the city. And, depending on how one looks at The Wire, this may be a precursor to how shows today spin off and create external worlds based on the original premise, such as what the Walking Dead and Game of Thrones do with online games and web series that further build external worlds the original series started. It’s hard to think of how that came to be without looking to The Wire. With its expansive layout, The Wire gave more power to and shaped what TV writers are capable of creating today.

This great expanse capitalizing on the drug trade serves to bring about an accurate portrayal of police detective work. Police procedurals tend to be so glorified in their subject’s work, where a bad guy does something, the cops solve the crime, bad guy goes to jail, and suddenly, the police are super well-funded and popular. The Wire, on the other hand, treats its police characters like shit. They have to go through red tape in order to get any work done. The purpose of The Wire is to drop all sleek and shine from police detective work. The show portrays the police in a more honest light: abusive, corrupt, disliked, and corner cutters, but also as people who have to be so in order to get any work done. The mass portrayal of the “system” shows these cops as real people, and only find themselves in situations of corruption because police have to follow orders, but these orders stem from the exact racist system that puts them in such abusive situations in the first place. This is no Brooklyn Nine-Nine or The Rookie. There are no good guys and bad guys. There are only flawed individuals trying to do good in a system that’s built to shoot down their idea of what’s “right.” We now see them as the enemy – individuals who misinterpret their power and responsibility in order to hold their authority superior to others. The majority of the public is now finally beginning to see what cops are actually like outside of a white, narrative television lens. When the pressure is put on the police, they begin to show their true colors.

Another area The Wire was miles ahead of their network counterparts in was their inclusion of LGBTQ characters. HBO was rather more honest in its portrayal of street gangsters and cops. But not only are these traits recognizable in the characters, they also serve to raise the stakes. Greggs is a detective trying to have a family with her wife, but her getting injured in the line of duty only puts her family at risk. Omar is also gay, but uses his partners as buffers between him and crime, always pinning them in the middle of violence. This show demonstrated that these characters are not wholly defined by their recognizable traits, but use these traits to further add to conflict.

The Wire also foresaw the demise of the news journalist pre-Twitter. In the final season, a Baltimore Sun reporter is lured by the idea of winning a Pulitzer. And by doing so, he subconsciously ends up fabricating news reports of a serial killer in order to gain momentum. But the media is just another institution The Wire sees as part of the system – they’re the last guardians of truth, what we expect to be reliable sources. But when that is compromised, the media turns itself into another veil of truth, fully knowing the public will intake whatever information is given to them. What is supposed to be a non-biased delivery of news, eventually also becomes corrupted by greed, lending itself to the cycle of lies that only allows for more lies to cover up the truth.

However, the real characters of the story are not the characters themselves, but the institutions – it’s a story of the Baltimore Police Department, and how it’s constrained by the limitations placed on it by politics. It’s a story of how the school system is an endless cycle doomed to fail that keeps replacing its cast. It’s a story of the ports and how drug money consumes and corrupts. It’s a story of the fall of the news journalist. It’s labeled as a “cop show,” but just as much as how Firefly is a western, or how Lost is scripted Survivor. The police is the setting, but it’s about the politics behind police work. It’s a rumination on modern society in the war on drugs. It points out the problems of the legal system, the pressure from superiors who don’t remember what police work is like, the societal issues that create the crime, and how for many people, especially those at the top, the justice system is just a numbers game. The cops portrayed are the way they are because the justice system built them to defend the corruption they’re meant to take down. That’s what The Wire represents: a broken system that only solves its problems temporarily through a feedback loop of abuse.

There’s a line in season 4 where Pryzbylewski says, “No one wins. One side just loses more slowly.” There are no “winners,” there is only the progress to be made, and those trying to do their best and willing to survive the system they’ve been spit out by. You don’t gain progress without someone falling behind. The game wins – everyone loses.