Note: This article contains donkey spoilers

In 2015, the German newspaper Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung published an article on why humans are fascinated with what they called “animal films,” or, films focusing on animals as their subjects rather than humans. It came to the conclusion that the phenomenon was attributed to the fact that, for the first time in history, a species (humans) has the ability to not only study and reflect on themselves, but to also document and research other species.

The cinema of 2022 seems to have brought that phenomenon to a heightened experience, albeit centered around an animal not so commonly focused on or documented. The donkey (Equus Asinus) seems to have taken the animal spotlight this year, particularly in films pushing for awards attention. Films such as Triangle of Sadness, Banshees of Inisherin, and EO have not just casted donkeys into the limelight, but gave them actual narrative-centric, stakes-heavy roles, even going so far as to make them protagonists in their own right.

But why now? Why this particular animal in this particular year? Well, the first thing one thinks of when they hear the word “donkey” is humor. On top of that, what donkeys also offer, or at least in these particular films, is companionship, thus making the animal great for sidekick roles that add a levity of humor (Shrek, etc.) 2021 and 2022 have had their fair share of ironic humor and wit. Comedy has become so “real” now, that what we used to joke about has now become commonplace. That’s not to say that the humor has gone, but our jokes have now become more of a reality than we previously thought.

With that in mind, no other animal embodies the levity of ironic humor quite like the donkey. Think of a donkey’s purpose: it’s indifferent, lazy, and doesn’t have much of a role on a farm aside from scaring off predators and pulling carts. Its only thought is to survive to the next day. Throughout pop culture, even stretching as far back as fairy tales and fables, the donkey has been the laughing stock of farm animals, which sadly gives it its gloomy reputation (Town Musicians of Bremen, Winnie the Pooh). But it also makes the perfect representation of ironic humor in 2022.

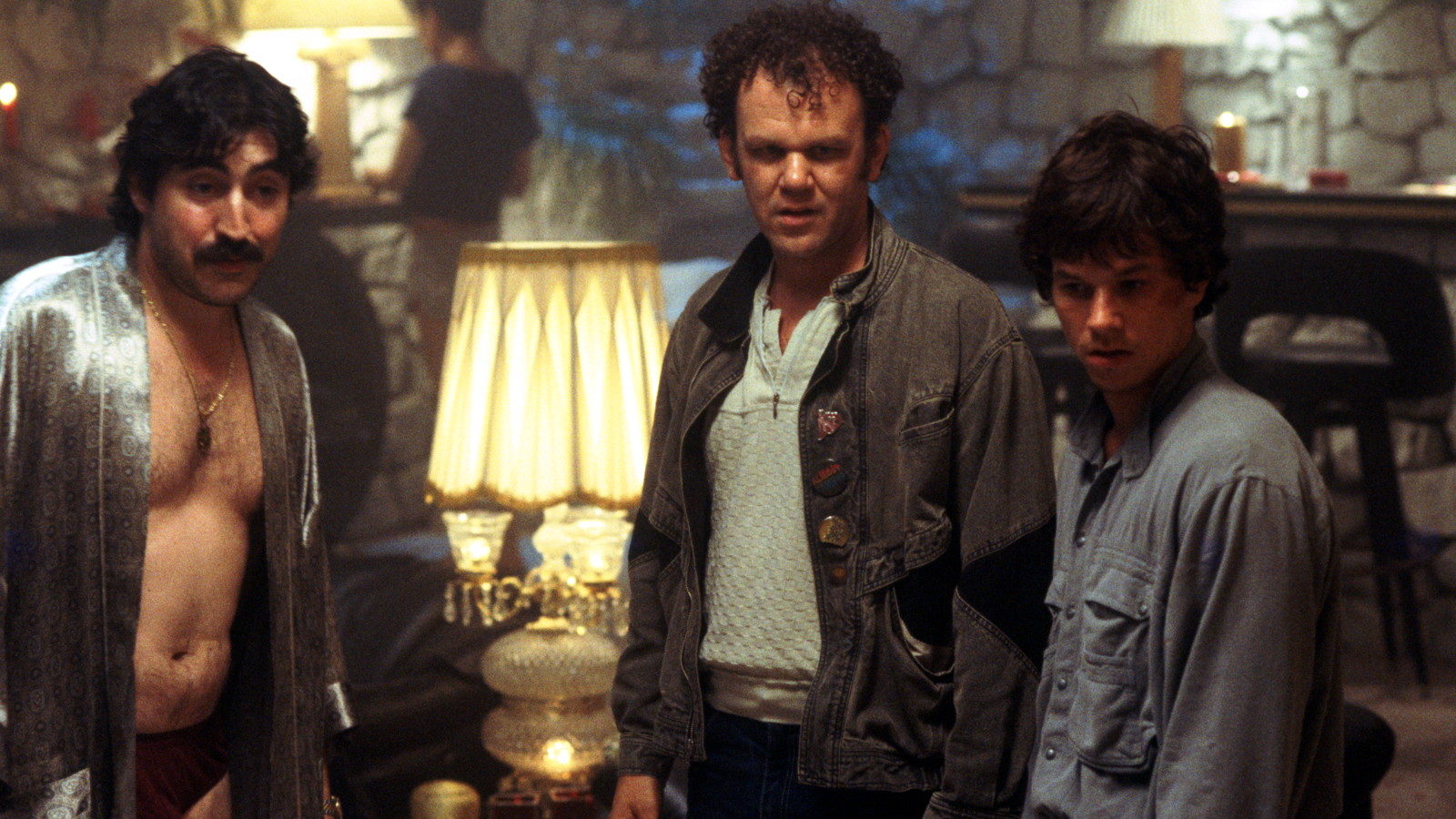

A donkey doesn’t make an appearance in Triangle of Sadness until about two-thirds through the film. But when it does, it’s used as a plot device in perhaps the most ruthless casting of the animal this year. When the upper echelon yacht cruise full of the rich and wealthy is shipwrecked, the affluent passengers are placed on an equal playing field with the yacht’s crew when they don’t know how to care for themselves, flipping the film’s theme of inequality upside down. Starving for food, they come across a donkey, and, well, you could guess what happens next….

The animal is definitely used in a darker comedic sense here, but why not any other animal? Would it have had the same effect had another animal been spared? The donkey tends to be the lowest on the totem pole. They’re a species that always gets the short end of the stick. And when it’s slaughtered, it’s merely a representation of irony dying, the cascading caste system that has descended upon the yacht-goers after being marooned.

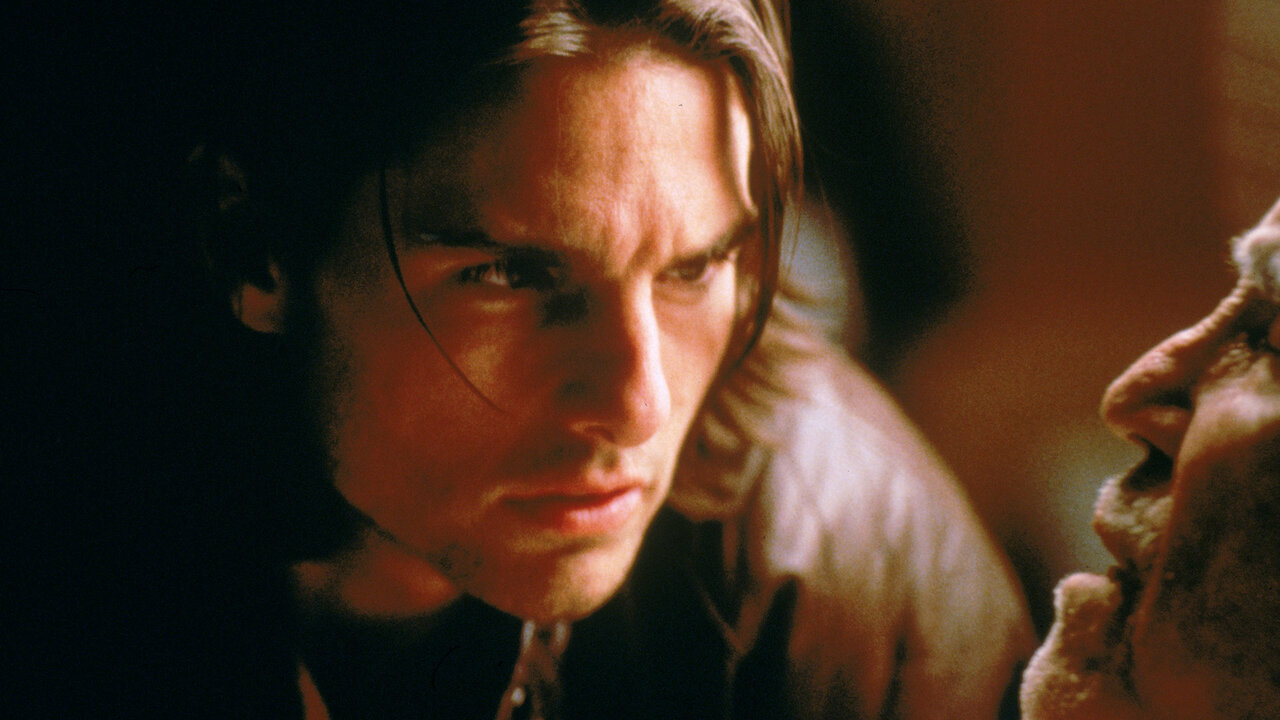

But pity humor isn’t the only trait the donkey inherited this year in cinema. The animal also took on the role of companionship, with Banshees of Inisherin going so far as to cast the animal in a supporting role as Pádraic Súilleabháin’s (Colin Farrell’s) sidekick. As everyone starts to leave Padraic’s life due to his toxic trait of being stagnant with his future he begins to become more and more attached to his donkey, the only familiar face that stays behind. Where Triangle sees the donkey as pity-less humor, Banshees breathes life into the animal by casting it through the lens of loyalty. However, as Padraic pushes the ones closest to him away, he also puts the last shred of his donkey’s loyalty at risk, which ultimately dies in the end as well.

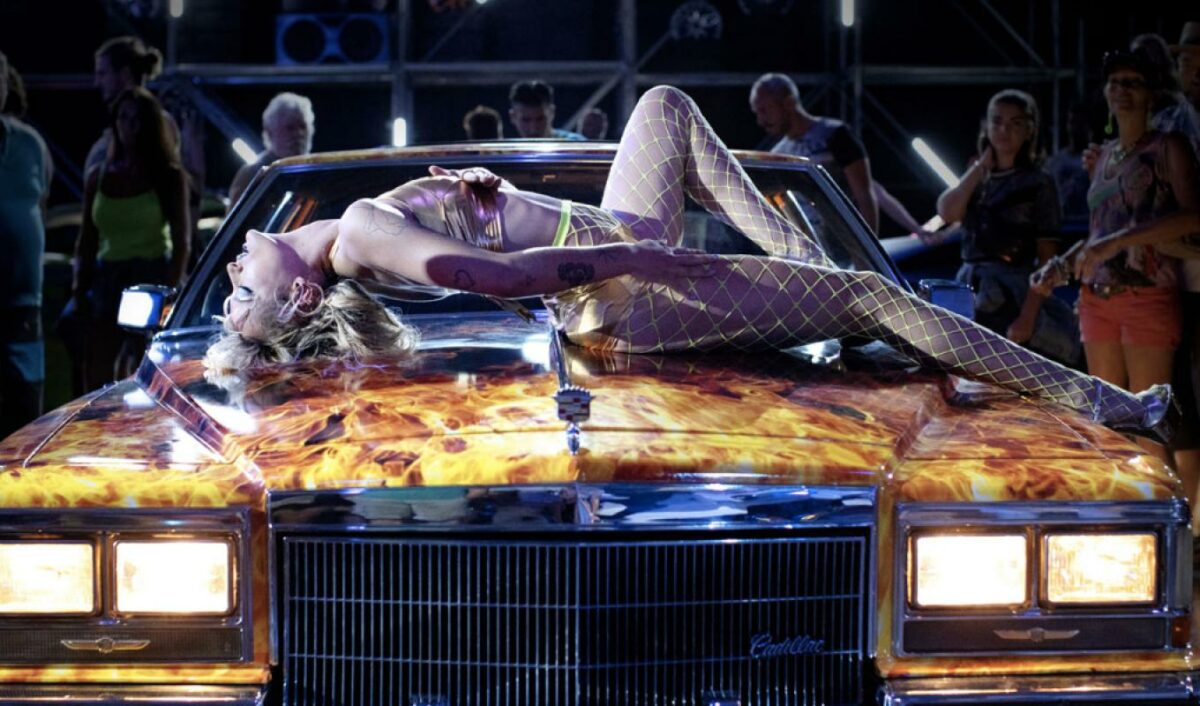

But aside from Donkeys perishing in the spotlight, the year in film has also casted them as main characters. The Jury Prize winner at this year’s Cannes film festival, EO follows a donkey that goes astray as it makes its way across Europe. It starts at a circus, where we see our donkey set free by an animal rights group and drift from one owner to the next, oblivious as to what’s carrying him each way. Along the way, he influences the outcome of a soccer match, becomes the mascot for a small town’s celebration, and is even brought into the company of Isabelle Huppert. But the most important element of this film is the stark contrast to our other two previous examples. What this film does that the other two don’t is give our donkey agency, an attempt to overcome the limitations placed upon itself, much like the preconceived notions humans already have when they hear the word “donkey.” Whereas Triangle and Banshees showed the fate of a donkey through a human lens, EO takes the POV of the animal, with the result being a surrealist, stylistic vision showing ultimately how humans interact with the animal kingdom.

Donkeys don’t tend to hold a soft spot for many people. Humans have put them to many uses over the years, including entertainment purposes. And these films go to show that they truly are at the mercy of the humans around them. People tend to argue what the most dangerous animal in the world is, when they’re blind to the fact that humans who are the most dangerous. To return to the article in Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, in our fascination with animal films, in our ability to record and document other creatures, we in turn often forget the implications and consequences of such actions, unaware of the interruptions we cause in their ecosystems. The cinema of 2022 seems to have flipped this perspective through empathy. In showing these consequences from the POV of the animal kingdom, the year gave us a necessary view of how, in studying other species, we also inadvertently record their demise.