Y’know, we never say this – but most of this year in film has been a bit of a lull. When 95% of the critically acclaimed films of 2024 come out in the least six weeks of the year, what does that say about the state of movies going into 2025? And what’s to blame? 2024 might be the year where we truly started to see the real turn and consequences of streaming, minimal release windows, and the “content” era. Here’s to hoping 2025 will keep the fire of cinema, theater etiquette, and theatrical movie going alive. Here are our top 10 films of 2024:

10. In a Violent Nature

Gone are the cliché screenwriting conventions. Gone is the damsel in distress. Gone is the overcooked, unnecessary exposition that we always tend to ignore when it comes to horror movies. Because here is a bona fide, balls to the wall slasher that’s shed of all the unnecessary homework and cuts right to the meat. Story? Surface level, Characters? Undeveloped. Concise ending? Not a chance. Shot primarily from the POV of our killer, simply named “Johnny,” In a Violent Nature turns the slasher genre (and its victims) inside out. After a group of campers impede on Johnny’s territory, all we’re told about these subjects is merely what we hear through Johnny’s ears. The result is a fun, unapologetic, gore-y, fresh take on a genre that’s been beat to death and tinkered with for decades. With some of the most memorable deaths in recent horror memory, In a Violent Nature replaces logic and reason with bold editing choices, a ghost-like Steadicam, and fun, new ways of mutilating punk-ass teenagers.

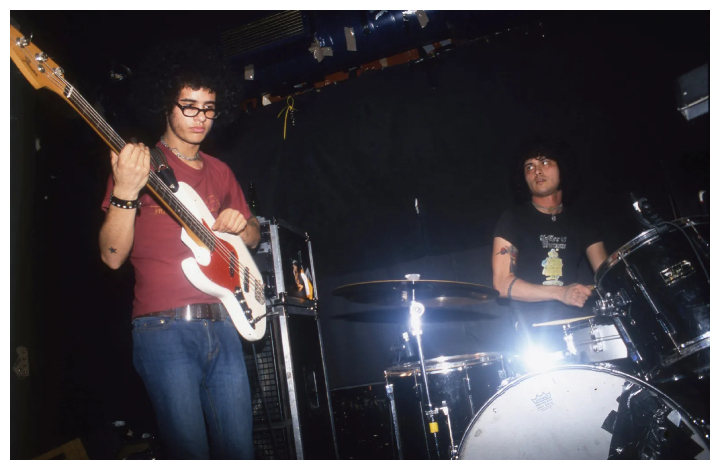

9. Omar and Cedric: If This Ever Gets Weird

With no sit-down interviews, strictly archival DV-cam footage, and two omniscient narrators, If This Ever Gets Weird chronicles the trials and tribulations of Omar Rodriguez-López and Cedric Bixler-Zavala, the two minds behind At The Drive-In and The Mars Volta.

Having been a partial fan of the bands, and even witnessed them live, I still was clueless about their bands’ origins, and was just as astonished to find out not only how many other bands they formed, but just how many of their bandmates passed away. And it’s even crazier to think that these guys were so good, they were able to “make it” not just once, not twice, but three or four more times after the demise of their previous bands. Music aside, the documentary dives into the cultural origins of the two musicians, demonstrating how their approach to songwriting is not to write “about” things, but to make music that comes from a place. Anyone familiar with their music can tell you that their creative output is rooted deep down in their Latino heritage. And for those who are not, If This Ever Gets Weird is an infectious, fascinating introduction to the two greatest modern minds in post-punk.

8. Tie: A Different Man and The Substance

Was 2024 secretly the year of Sebastian Stan? After years of starring in Marvel movies and cash grab limited series, it appears he’s finally found the niche filmmaking his talents can truly flourish in. A man with a facial deformity who loathes how the attractive cruise through life decides to undergo a facial reconstruction surgery to experience the luxury for himself. It’s hard not to compare A Different Man to another film this year – The Substance – two films that are two sides of the same coin: they both touch on the same themes, and treat their subjects with the utmost cruelty. However, A Different Man dives just a bit deeper. Whereas The Substance wears its conflict on its sleeve, A Different Man keeps its just beneath the surface, but still externalizes it enough to drive the story forward while keeping the film’s air of mystery. With a standout performance from Adam Pearson (who, fingers crossed, gets all the recognition he deserves), A Different Man is one of the bigger head scratcher films of 2024. Not from confusion, but from the profound observance of just how much the attractive really do have it easier.

On the other side of the coin, The Substance explores eternal youth. In her second feature film, Coralie Fargeat single handedly resuscitates Demi Moore’s career with a film that’s everything A Different Man is not: over-the-top, unsubtle, and very loud. Yet, it’s hard to not keep them in the same conversation with each other. With a sound design and score that’s louder than most war films, The Substance feels like a film turned inside out, much like its subjects – the elements that are typically explored beneath a film’s surface seem to have risen to the top. Perhaps the most visceral and tangible of all the films of 2024, The Substance carries itself with its shock value, whereas A Different Man grounds itself with its mysterious interiority.

6. A Complete Unknown

Wow, this guy was a real asshole wasn’t he?

The biopic on the one man we thought we’d never see a biopic about, A Complete Unknown covers Bob Dylan’s rise from his arrival in New York in 1961 to his famous Newport Folk Festival fiasco in 1965. Taken into account are his relationships with Bob Seeger and Woodie Guthrie, his pen pal-ship with Johnny Cash, and his tumultuous romance with Joan Baez. Critics will complain about how we’re spoon fed such information, or about how we could’ve learned all of this from his Wikipedia page, or how it’s a biopic of “reaction shots.” Narratively, however, it all works. The cast of players in these roles all push Dylan towards being put in a categorical box. And that’s what this film is truly about: expectations, and how “contrarian” Dylan was to never be able, or want to, abide by them. Chalamet and Mangold work in harmony here to seamlessly show Dylan’s transformation to who he’d become by the mid-60s. The change in sound, attire, attitude… it all proves to show that the director and crew did their job to capture who Dylan was at the most pivotal point in his career.

5. Kneecap

Language as a means of preservation, language as a heritage, language as a weapon. Spoken for the majority in Gaelic, Kneecap follows the rise of the real-life Irish hip-hop group of the same name. Faced with oppression for speaking only in their native tongue in a time where Gaelic had yet to be recognized as an official language in Northern Ireland, Kneecap ingeniously uses its language not just as a way of communicating dialogue, but as a vessel of change and rebellion. It’s punk rock cinema in that the medium is used as a means to push toward tolerance. Combined with a badass soundtrack and impressive performances (even if they were playing themselves), Kneecap is among the most watchable, if not enjoyable, films of 2024.

4. Wicked

Over 20 years since its premiere, Wicked finally received the film adaptation it deserved in 2024. And for better or worse, it was worth the wait. One of the most hyped films of 2024 (if not the most hyped), Wicked managed to deliver on every level of production. Even those not familiar with the musical (i.e. this writer) would be hard pressed to find any inch of this film that doesn’t shimmer. Regardless of how you feel about an Ariana Grande and Cynthia Erivo musical, the roles are perfectly cast as if each actor was born to play their respective roles. With minimal air bubbles, minimal downtime, every minute of the film’s nearly three hour runtime is watchable, which will probably make this film the awards darling everyone assumed it would be.

3. Conclave

Electing a pope is arguably the most secretive election process in the world. So it’s no surprise that a film like Conclave immediately draws you into a fascination based on the premise alone. It’s a process and culture foreign to most people (myself included), but that’s exactly what makes it so infectious: there’s a systematic working and language to it all that’s hard to break into, but that only compels one to discover more about it. Unsurprisingly, the process is just as flawed and tampered just like many other election processes in the world. Following a British Cardinal (Ralph Fiennes) overseeing the selection of a new Pope, Conclave may be viewed form the outside-in as homework, or medicine we’re forced to take. But it’s anything but. A la Spotlight, Conclave grows into a riveting papacy thriller filled with twists. Isabella Rossellini makes a comeback out of nowhere, and Fiennes gives his best performance in a decade since Grand Budapest Hotel. But it’s the ensemble of players that carry this film’s vibrancy, all playing against Fiennes’ crisis of faith as we discover their hidden agendas. Conclave takes unfamiliar subject matter and interprets it as an espionage thriller, and I’d be lying if I said I wasn’t just entertained by it, but downright, absolutely fascinated.

2. Challengers

Of all the films of 2024, Challengers is probably the best overall produced film of the year. From its casting all the way down to its editing, the film explores the dimensions not just of its protagonist (we’ll let you decide who that is) but all three subjects of its love triangle. And never has a film made a sport like tennis look so sexy and filled with homoerotic tension. Every element of this film is operating at its peak: Nine Inch Nails compose their best score since The Social Network 15 years ago, Justin Kuritzkes’ script does just enough callbacks to show how much time and work was put into it, and Sayombhu Mukdeeprom’s cinematography defines the spatial geography between our three leads. Out of all the projects Luca Guadadnino did this year, Challengers might be through and through his most fully baked: the POV of the tennis ball, the see-through tennis court constructed to see the players from beneath… it all contributes to the motion and drama of the sport. But don’t ask me. Just go to your local athletic club and see how many Gen Z’ers signed up for tennis lessons, or better yet, how many couples signed up looking for their third.

1. Nickel Boys

Shot entirely in first-person POV, Nickel Boys follows the perspectives of two black teenagers in Jim Crow south at a reform school, alternating between each one. Think the opposite of The Zone of Interest – whereas last year’s film forced the viewer to feel unattached from the events on screen, Nickel Boys sits you down to feel all of it. Spellbinding images that shouldn’t work when spliced together create magic, and lighting that doesn’t intrude on its subjects feels motivated without the use of traditional coverage. Nickel Boys is not just an intimate, searing portrait of two boys being punished for the color of their skin, but it’s a different approach in making a film altogether. Editing, cinematography, and director RaMell Ross’s approach all seem to be working in perfect harmony here. Rarely do you see the two subjects in the same frame (perhaps only once?), but it’s in these moments where, as cinematographer Jomo Fray puts it, “I feel like I see God.” You’ll swear there’s some form of a higher power at work. Not just in our characters’ journeys, but in how this film was made.