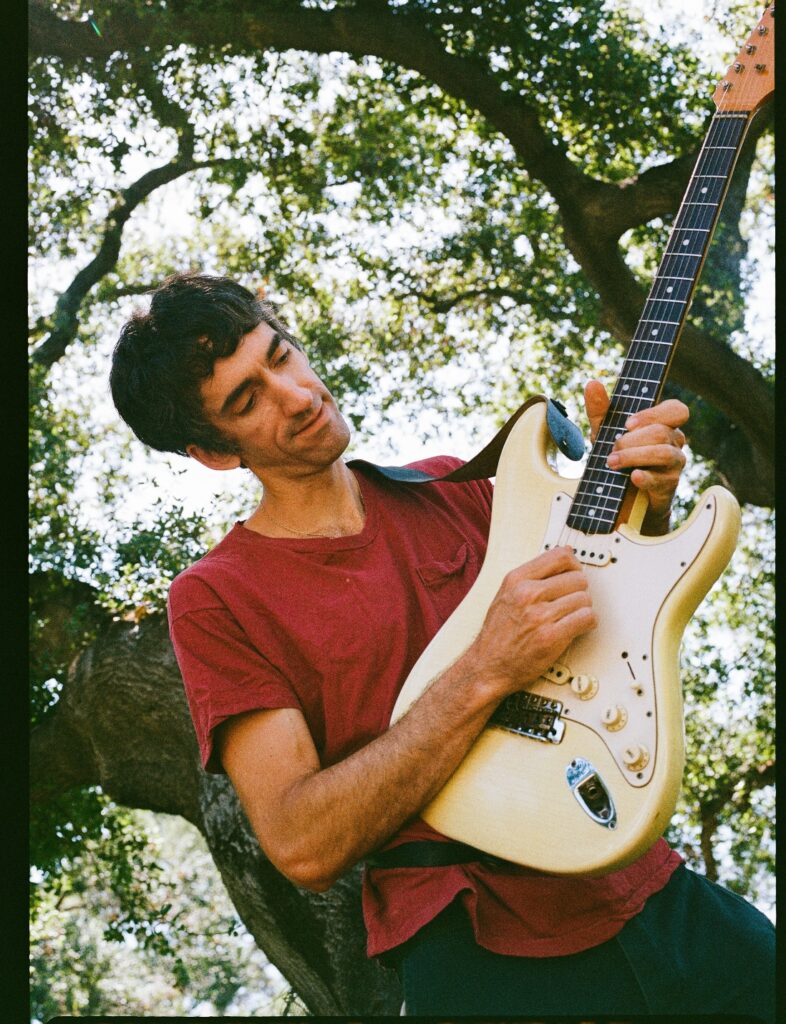

Delicate Steve is merely an illusion. The moniker of instrumental guitarist Steve Marion has been mythologized much in the past decade. Having worked with Paul Simon, the Black Keys, Dirty Projectors, and been a staple for some time now in contemporary music as a studio musician, it’s a miracle he hasn’t yet become a household name. And if his music was a little more in the tradition of “singer/songwriter,” you’d might even hear it on the radio.

And yet, despite the band being himself, Marion remains detached from Delicate Steve. Keeping himself at a distance, he chooses it to be a project that’s more of an extension of himself, something of bottomless intrigue, something he could rely on to constantly further discover himself.

“I couldn’t tell you how anything works,” Marion confesses. “I don’t pay much attention to ‘why’ or ‘why not.’ If one other person cares about what you do, you go from zero to one, and you kind of observe that. And that might be a hundred people who care about you, or a thousand… if you do it long enough, not everyone cares about everything you do. And that’s totally okay. That’s natural. I think, if you’re lucky, you learn to kind of detach from it a little bit.

“In particular with just making music and making a song… It’s not like if you just try harder you’re going to make a greater song. So I do think there’s some part of it that is inverse to how much you actually ‘try.’ It can be sort of counter-productive the more you’re ‘trying.’ So I think it’s helpful to try to relinquish control and just let the creativity do its thing. That’s all you can do, is do the work and show up and put the shows on the calendar.”

Coming up in the early 2010s amongst the bustling Brooklyn scene at the time, Delicate Steve would often find himself playing to his contemporaries: Dirty Projectors, Grizzly Bear, TV on the Radio… but it wasn’t until after he signed to David Byrne’s label, Luaka Bop, where a press release from none other than journalist Chuck Klosterman of Spin Magazine shot Delicate Steve into the stratosphere. The release described the band as “a hydro-electric Mothra rising from the ashes of an African village burned to the ground by post-rock minotaurs,” with music that would “make you the happiest person who has never lived,” and other such hyperboles.

“Do you think more people listened to you [because of the press release] than would have otherwise?” we ask.

“Definitely,” he affirms. “And I learned a lot from the experience. It was actually my label’s idea. But I reluctantly said yes [to the press release] because it just sounded a little out of my comfort zone and weird and next thing you know it really made a difference. So, having an experience like that kind of early on where you’re able to see outside of yourself and just kind of see something like that take off in the world, it was eye opening.”

This enigmatic approach to marketing yourself, however, has become somewhat non-existent today. Or yet, maybe it’s totally abundant. In the days where Spotify bios weren’t a conscious thought, it was strategies like these that got outlets’ and labels’ attentions. Today, anyone can describe or portray themselves in whatever esoteric manner they please. But when everyone’s trying to be more enigmatic than the next, it’s almost like screaming into a void.

“Do you think an instrumental band can take the same route you took today and still be successful?” we follow up.

Marion ponders, “Umm… I don’t know. I mean there are kind of these instrumental bands that sort of came about after whatever my time was… But I doubt anyone’s even thinking of [those bands] as instrumental bands. It’s maybe just a vibe for people. And it’s almost less about the fact that there’s no singing, to me, and more about the fact that they have such a strong aesthetic – visually, sonically – so I think that’s really what people are gravitating towards.

“Take a band like Khruangbin, who are super successful, and it’s not just one person. I would say they have a ‘friendly’ sound and a ‘friendly’ look collectively. So whatever I’m calling that, that’s kind of like the future. Do they happen to not have a singer and be ‘instrumental?’ Yeah. Do I also not have a singer and happen to be instrumental? Yeah… But I don’t identify as an instrumental band myself either. When I think ‘instrumental band,’ to me, that reminds me of finding out about Booker T. & the M.G.’s… or even more modern instrumental bands that I grew up listening to like Explosions in the Sky or Godspeed You! Black Emperor. Instrumental is a weird sort of categorization.”

An experience outweighs what we think is lacking in what a traditional band would be. However, when it comes to Delicate Steve, Marion’s guitar is his voice. Unlike following every other teenage guitar player in the U.S. in idolizing guitar virtuosos like Steve Vai and Joe Satriani, Marion takes his inspiration from vocalists such as Nina Simone and Otis Redding – vocalists who use their voice as an extension of themselves.

“I mean… before this band I was a guitar player to my core, which I have identified less with since kind of figuring out this band… which feels more like a songwriter without using my human voice – that’s how I describe my band. I’m a huge Duane Allman fan. He’s like my number one. And even though that band is very bluesy, blues-rock and jam-y, he sort of transcends all that. And I just like how he represented that as well – somebody that kind of transcends the genre that they’re mostly operating in.”

“What would you say to someone who claims no one’s done anything original with the guitar in the past 20 years?” we ask.

“Somebody said this to me a few years ago,” Marion goes in: “‘[the guitar] is still an extremely futuristic instrument, that is made out of wood, steel strings, with the help of magnets, which vibrate to create a sound that gets amplified through a speaker…’ and I’m playing one from 1966. Everyone’s so interested in things being organic, and not being processed, and being all natural. A guitar, compared to a computer or your little electronic keyboard, is sort of as organic as it comes. So I think there’s still a lot of potential there. Especially now with the heightened focus on ‘vibes’ of things, and how people sort of look and how things sound. You could just be a singer-less guitar player and change the world I think.”

But with the emergence of contemporary guitar virtuosos such as Mk.gee and Sam Fender, who have introduced their own radical approaches to the instrument, perhaps today the guitar is being assigned a new definition in how it’s used.

“Do you think the ‘guitar virtuoso’ phase is coming back?” we inquire.

Marion muses, “I don’t know. I would be the last person to know about any of this. But I can see why people gravitate to that now. Like for me, I know I’m good in my own unique way, but I’m never really thinking about that. And I’m sure Mk.gee, even though I can tell he is virtuosic in this way, he’s probably never thinking about it himself either. Again, relinquishing control. You really can’t tell, especially nowadays, what’s going to become popular or not. So yeah, when the day comes when there’s more instrumental bands then there are singers, then I’ll really be blown away. If that ever happens.”

Marion has found himself in an extremely convenient and fortunate position to be able to distance himself from his signature project; an attitude so blasé, that his mindset almost carries him through his career. With minimal promotion, minimal social media engagement, it’s rare for an artist to gain such traction from being so detached, especially for an instrumental guitar player.

“It feels healthier to just… stay in your little universe, and do you what you do. And if you’re lucky, you’re not paying attention to as much as possible, really.”

Delicate Steve can currently be heard on Joe Cappa’s Haha You Clowns, airing now on Adult Swim, and will embark on a Spring tour beginning in Portland, Oregon on March 27th. His latest album, Luke’s Garage, is out now via Have Fun Thinking.

Photos courtesy of Sheva Kafai